Chemotherapy Side Effects

Different chemotherapy drugs cause different

side effects, and some people may have very few. Cancer treatments cause

different reactions in different people and any reaction can vary from

treatment to treatment.

It may be helpful to remember that almost all

side effects are only short-term and will gradually disappear once the

treatment has stopped.

The main areas of your body that may be

affected by chemotherapy are those where normal cells rapidly divide and grow,

such as the lining of your mouth, the digestive system, your skin, hair and

bone marrow (the spongy material that fills the bones and produces new blood

cells).

Possible side effects of some chemotherapy drugs

|

Tiredness

Bone marrow

Alteration of kidney

function

Nausea and vomiting

Loss of appetite |

Diarrhoea

Constipation

Your mouth

Taste changes

Weakness |

Hair loss

Effects on the nervous

system

Changes in hearing

Skin changes

Effects on the nerves

|

Tiredness

While having chemotherapy and for some time afterwards you may feel

very tired (fatigued) and have a general feeling of weakness. It is

important to allow yourself plenty of time to rest.

The

tiredness will ease off gradually once the chemotherapy has ended,

but some people find that they still feel tired for a year or more

afterwards. The

tiredness will ease off gradually once the chemotherapy has ended,

but some people find that they still feel tired for a year or more

afterwards.

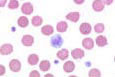

Bone marrow

Chemotherapy can

reduce the number of blood cells produced by the bone marrow. Bone

marrow is a spongy material that fills the bones and contains stem

cells, which normally develop into the three different types of

blood cell.

The cells produced by bone marrow:

►white blood

cells are essential for fighting infections

►red blood cells contain haemoglobin to carry oxygen round the

body

►platelets help to clot the blood and prevent bleeding.

White blood cells

If the number of white cells in your blood is low you will be more likely to get

an infection as there are fewer white cells to fight off bacteria. If your

temperature goes up, or you suddenly feel unwell, even with a normal

temperature, contact your doctor or the hospital straight away. Most hospitals

consider a temperature above 38°C (100.5°F) to be high, although some hospitals

use a lower or higher temperature.

Your

regular blood tests will also show the number of white cells in the blood. If

you get an infection when your white blood cell level is low you may need to

have antibiotics. Your

regular blood tests will also show the number of white cells in the blood. If

you get an infection when your white blood cell level is low you may need to

have antibiotics.

These may be given intravenously (into the vein) in the chemotherapy day unit or

as tablets which can be taken at home. You may need to be admitted to hospital

for the antibiotic treatment.

In some circumstances, drugs called growth factors can help your bone marrow to

make more white blood cells. Growth factors are special proteins, normally made

in the body, which can now be produced in the laboratory.

Blood cells are usually at their lowest level from 7 to14 days after the

chemotherapy treatment, although this will vary depending on the type of

chemotherapy.

Red blood cells

If the level of red blood cells (haemoglobin) in your blood is low you may

become very tired and lethargic. As the amount of oxygen being carried around

your body is lower, you may also become breathless.

These are all symptoms of anaemia - a lack of haemoglobin in the blood. People

with anaemia may also feel dizzy and light-headed, and have aching in their

muscles and joints.

During chemotherapy you will have regular blood tests to measure your

haemoglobin. A blood transfusion can be given if your haemoglobin is low. The

extra red cells in the blood transfusion will very quickly pick up the oxygen

from your lungs and take it around the body. You will feel more energetic and

any breathlessness will be eased.

Sometimes a drug called erythropoietin can be used to stimulate the bone marrow

to produce red blood cells more quickly. Erythropoietin is given as an injection

just under the skin of the thigh or abdomen, from one to five times a week.

Platelets Platelets

If the number of platelets in your blood is low you may bruise very easily and

may suffer from nosebleeds or bleed more heavily than usual from minor cuts or

grazes. If you do develop any unexplained bleeding or bruising you need to

contact your doctor or the hospital straight away, and you may need to be

admitted to hospital for a platelet transfusion.

A fluid containing platelets is given by drip into your blood. These platelets

will start to work immediately, to prevent bruising and bleeding.

Your regular blood tests will also be used to count the number of platelets in

your blood. If your platelets are low, take care to avoid injury - for example,

if you are gardening wear thick gloves.

Alteration of kidney function

Some chemotherapy drugs such as cisplatin and ifosfamide can cause damage to the

kidneys. In order to prevent kidney damage, fluids may be given by drip into

your vein for several hours before you have the treatment and your kidney

function will be carefully checked by blood tests before each treatment.

Nausea and vomiting

Some chemotherapy drugs can make you feel sick (nausea), or actually be sick

(vomit). Many people have no sickness, but for those who do there are now very

effective treatments to prevent and control it, so it is much less of a problem

than it was in the past.

If you do feel sick, it will usually start from a few minutes to several hours

after the chemotherapy, depending on the drugs you are having. The sickness may

last for a few hours or, rarely, for several days.

Your

doctor can prescribe anti-sickness drugs (anti-emetics) to stop or reduce this

side effect. Anti-emetics may be given by injection with the chemotherapy and as

tablets to take at home afterwards. Your

doctor can prescribe anti-sickness drugs (anti-emetics) to stop or reduce this

side effect. Anti-emetics may be given by injection with the chemotherapy and as

tablets to take at home afterwards.

Steroids can also be helpful in reducing nausea and vomiting. Given in this way,

they often give a sense of well-being, as well as helping to reduce feelings of

sickness and loss of appetite.

Diarrhoea and constipation

Some chemotherapy drugs can affect the lining of the digestive system and this

may cause diarrhoea for a few days. Some chemotherapy drugs (or drugs given to

control side effects such as nausea) can cause constipation.

If you have any diarrhoea or constipation, or are worried about the effects of

chemotherapy on your digestive system, see your doctor or chemotherapy nurse to

discuss any problems you may have.

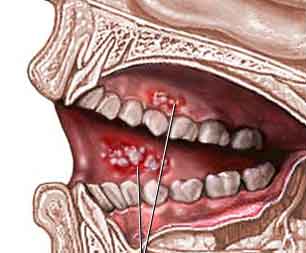

Your mouth

Some drugs can cause a sore mouth, which may lead to mouth ulcers. If this

happens it is usually about 5 to 10 days after the drugs are given and will

clear up within three to four weeks. Your doctor can prescribe mouthwashes to

help. The mouth ulcers can become infected, but your doctor can give you

treatment to help prevent or clear infection. Cleaning your teeth regularly and

gently with a soft toothbrush will help to keep your mouth clean.

If your mouth is very sore, gels, creams or pastes can be used to paint over the

ulcers to reduce the soreness. Your cancer specialist can tell you about these.

Taste changes

Chemotherapy can cause your taste to change; food may taste more salty, bitter

or metallic. Normal taste will come back after the chemotherapy treatment

finishes.

Your hair

Complete or partial hair loss can occur with some chemotherapy drugs and can be

very distressing. Some drugs cause no hair loss or the amount of hair lost is so

slight it is hardly noticeable.

Some chemotherapy can damage hair and make it brittle. If this happens the hair

may break off near the scalp a week or two after the chemotherapy has started. The amount of hair lost, if any, depends on the type of drug or combination of

drugs used, the dose given and the person's individual reaction to the drug. If

hair loss happens it usually starts within a few weeks of beginning treatment,

although very occasionally it can start within a few days. Underarm, body and

pubic hair may be lost as well. Some drugs also cause loss of the eyelashes and

eyebrows. If you do lose your hair as a result of chemotherapy, it will grow

back once you have finished your treatment. See

HAIR LOSS page

The amount of hair lost, if any, depends on the type of drug or combination of

drugs used, the dose given and the person's individual reaction to the drug. If

hair loss happens it usually starts within a few weeks of beginning treatment,

although very occasionally it can start within a few days. Underarm, body and

pubic hair may be lost as well. Some drugs also cause loss of the eyelashes and

eyebrows. If you do lose your hair as a result of chemotherapy, it will grow

back once you have finished your treatment. See

HAIR LOSS page

Skin changes

Some drugs can affect your skin. These may make your skin become dry or slightly

discoloured and may be made worse by swimming, especially if there is chlorine

in the water. Any rashes should be reported to your doctor.

The drugs may also make your skin more sensitive to sunlight, during and after

the treatment. Protect your skin from the sun by wearing a hat and sunglasses,

covering skin with loose clothing and using sunscreen cream on any exposed

areas.

Your nails

Your nails may grow more slowly and you may notice white lines appearing across

them. Sometimes the shape or colour of your nails may change: they may become

darker or paler. False nails or nail varnish can disguise white lines. Your

nails may also become more brittle and flaky.

Effects on the nerves

Some chemotherapy drugs can affect the nerves in the hands and feet. This can

cause tingling or numbness, or a sensation of pins and needles. This is known as

peripheral neuropathy. Let your doctor know if it occurs.

Usually it gradually reduces when the chemotherapy treatment ends but if it

becomes severe it can damage the nerves permanently. Your doctor will keep a

close check on you and may need to change the chemotherapy drug if the problem

is getting worse.

Effects on the nervous system

Some drugs can cause feelings of anxiety and restlessness, dizziness,

sleeplessness or headaches. Some people also find it hard to concentrate on

anything.

Changes in hearing

Some chemotherapy drugs can cause loss of the ability to hear high-pitched

sound. They can also cause a continuous noise in the ears known as tinnitus,

which can be very distressing. Let your doctor know if you notice any change in

your hearing.

Social life

You may be able to go to work and carry

on with your social activities as usual, but may need to take rests during the

day or shorten your working hours.

Some people feel very tired during

chemotherapy. This is quite normal and may be caused by the drugs themselves and

your body fighting the disease, or may simply be because you are not sleeping

well.

For someone who normally has a lot of

energy, feeling tired all the time can be very frustrating and difficult to cope

with. The hardest time may be towards the end of the course of chemotherapy.

Try to cut down on any unnecessary

activities and ask your family or friends to help you with jobs such as shopping

and housework. It is important not to fight your tiredness. Give yourself time

to rest and if you are still working see if it is possible to reduce your hours

while you are having treatment.

If you are having problems with

sleeping, your GP may be able to prescribe some mild sleeping tablets for you.

While you are having chemotherapy you

may find that you cannot do some of the things you used to take for granted. But

you needn't stop your social life completely.

Depending on how well you feel, there is

no reason to stop going out or visiting friends, especially if you can plan

ahead for social occasions. For example, if you are going out for the evening,

you could make sure that you get plenty of rest during the day so you have more

energy for the evening.

If you are planning to go out for a

meal, you may find it helpful to take anti-sickness tablets before you go and to

choose your food carefully from the menu.

If you have an important social event

(such as a wedding) coming up, discuss with your doctor whether your treatment

can be altered so that you can feel as well as possible for the occasion.

Alcohol

For most people, having the occasional alcoholic drink will not affect their

chemotherapy treatment, but it is best to check with your doctor beforehand.

Holidays and vaccinations

If you are going abroad on

holiday, it is important to remember that you should not have any 'live virus'

vaccines while you are having chemotherapy.

These include polio, measles, rubella

(German measles), MMR (the triple vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella), BCG

(tuberculosis), yellow fever and typhoid medicine. There are, however, vaccines

which you can have, if necessary.

If you are travelling abroad ask your

doctor whether you should have other vaccines such as diphtheria, tetanus, flu,

hepatitis B, hepatitis A, rabies, cholera or typhoid injection.

Sometimes people who have, or have had,

cancer can find it difficult to get travel insurance to travel abroad.

Will

chemotherapy affect my sex life?

Some people go through their chemotherapy

with their usual sex lives unaffected. On the other hand, some people find

that their sex lives are temporarily or permanently changed in some way due

to their treatment.Any

changes that occur are usually temporary, and should not have a long-term

effect on your sex life. For example, there may be times when you just feel

too tired, or perhaps not strong enough for the level of physical activity

you are used to during sex.

If your treatment is making you feel

sick, you may not want to have sex at all for a while. Anxiety may also play a large part in

putting you off sex. Often this anxiety may not seem directly related to

sex; you may be worried about your chances of surviving your cancer, or how

your family is coping with the illness, or about your finances. Stresses

like these can easily push everything else, including sex, to the back of

your mind.

Any such changes are usually

short-term and not serious. There is no medical reason to stop having sex at

any time during your course of chemotherapy. It is perfectly safe, and the

chemotherapy drugs themselves will have no long-term physical effects on

your ability to have and enjoy sexual activity. Any changes in your sex life are

unlikely to last long.

It is thought that chemotherapy drugs

cannot pass into semen or vaginal fluids. However, for people having

chemotherapy most hospitals advise the use of condoms during sexual activity

for up to a few days after the treatment has been given. This is to prevent

any possible problems for their partner.

It is important to take good

contraceptive precautions whilst having chemotherapy, as chemotherapy

drugs can harm the baby if pregnancy occurs. For this reason, your doctor will

advise you to use a reliable method of contraception (usually 'barrier'

methods - such as condoms or the cap) throughout your treatment and for

a few months afterwards.

The only exception may be women

whose chemotherapy has brought on an early menopause. These women will

experience symptoms usually associated with the menopause, which may

include dryness of the vagina and a decreased interest in sex.

If you are worried that the

chemotherapy could affect your sex life, try to discuss your worries

with your cancer specialist before your treatment starts. Your doctor

should be able to tell you about the side effects your treatment may

cause and you can then talk about the main effects of these, if any, on

your sex life.

You need to know about all aspects

of your treatment, and if sex is an important part of your life, it

matters that you should be fully aware of any possible changes. It may help if you can discuss

your feelings and any worries with your partner. Even though it is

unlikely that chemotherapy will cause any problems with sex, your

partner may still have some anxieties and may have been waiting for a

sign from you to show that it is all right to discuss them. Perhaps your

partner could join you if you decide you want to talk to your doctor.

Overcoming any problem, sexual or

otherwise, may seem like an uphill struggle when you are also trying to

come to terms with your cancer and cope with chemotherapy. Remember that

most side effects from chemotherapy that may affect your sex life, such

as tiredness or sickness, will gradually wear off once your treatment is

finished.

Will

chemotherapy make me infertile?

Unfortunately some chemotherapy

treatments may cause infertility. Infertility is the inability to become

pregnant or to father a child and may be temporary or permanent,

depending on the drugs that you are having.

It is strongly advised that you

discuss the risk of infertility fully with your doctor before you start

treatment. If you have a partner he or she will probably wish to join

you at this discussion so you can both be aware of all the facts and

have a chance to talk over your feelings and options for the future.

Although chemotherapy can reduce

fertility it is quite possible for a woman having chemotherapy to become

pregnant during the treatment. The side effects of chemotherapy, such as

sickness and diarrhoea, can make the pill less effective. Female

partners of a man having chemotherapy may also become pregnant.

Pregnancy should be avoided during chemotherapy in case the drugs harm

the baby.

Female fertility

Some drugs will have no effect on your fertility, but some may

temporarily or permanently stop your ovaries producing the eggs which

can be fertilised by the sperm during sex.

If this happens it means,

unfortunately, that you can no longer become pregnant and it will also

bring on symptoms normally associated with the change of life (the

menopause).

During chemotherapy your monthly

periods may become irregular and stop and you may have hot flushes, dry

skin and dryness of the vagina. Some women's ovaries will start

producing eggs again once the treatment ends. If this is the case, the

infertility will have been short-term. Your periods will return to

normal after the treatment finishes. This happens in about a third

of women. Usually, the younger you are, the more likely you are to have

normal periods again and still be able to have children once the

chemotherapy has ended.

Depending on the type of cancer

you have, your doctor may be able to prescribe hormone tablets to

help relieve the menopausal side effects. The hormones, unfortunately,

will not enable you to start producing eggs again and so cannot prevent

infertility.

Pregnancy and cancer

If you are pregnant before

your cancer is diagnosed and your chemotherapy starts, it is very

important to discuss with your doctor the pros and cons of continuing

with your pregnancy.

It is sometimes possible to

delay starting chemotherapy until after the baby is born, depending on

the type of cancer you have, the extent of the disease, how advanced the

pregnancy is and the particular chemotherapy you will be having.

You will need to talk to your

doctor about your pregnancy and be sure you are fully aware of all the

risks and alternatives before making any decisions.

Male fertility

Some chemotherapy drugs will have no effect at all on fertility, but

some may reduce the number of sperm produced or affect their ability to

reach and fertilise a woman's egg during sex.

Unfortunately, this means you

may no longer be able to father children. However, you will still be

able to get an erection and have an orgasm as you did before you started

your treatment.

You should use a reliable

barrier method of contraception all through your treatment.

If you have not completed your

family before you need to start chemotherapy, you may be able to bank

some of your sperm for later use.

If this is possible in your

case, you will be asked to produce several sperm samples over a few

weeks. These will then be frozen and stored so that they can be used

later to try to fertilise an egg and make your partner pregnant.

The pregnancy should then carry

on as normal. You may be charged a fee for sperm storage, and also

for the infertility treatment.

If the chemotherapy does cause

infertility, some men will remain infertile after their treatment has

stopped while others will find their sperm returns to normal levels and

their fertility comes back.

Sometimes it may take a few

years for fertility to return. Your doctor will be able to do a sperm

count for you when your treatment is over to check your fertility.

Teenage boys should also be

aware of the infertility risk so that, if possible, their sperm can be

stored for later years.

Your feelings about

infertility

Some people are devastated

when they discover that the treatment they need for their cancer will

also mean they can no longer have any children. If you had been planning

to have children in the future or to have more children to complete your

family, infertility will be very hard to come to terms with.

The sense of loss can be very

painful and distressing for people of all ages. Sometimes it can feel as

though you have actually lost a part of yourself.

You may feel less of a man or

less feminine because you can't have children. Women especially may be

distressed, and resentful that the drugs may cause bodily changes, such

as the menopause, which can further undermine their self-confidence.

People vary in their reactions

to the risk of infertility. Some people may shrug it off and feel that

dealing with the cancer is more important. Others may seem to accept the

news calmly when they start treatment and find that the impact doesn't

hit them until the treatment is over and they are sorting out their

lives again.

There is no right or wrong way

to react. You may want to discuss the risks and all your options with

your doctor before you start treatment. You may also need an opportunity

to talk to a trained counsellor about any strong emotions which threaten

to become too much for you.

Your partner will also need

special consideration in any discussions about fertility and future

plans. You may both need to speak to a professional counsellor or

therapist specialising in fertility problems. They can help you to come

to terms with your situation.

|