|

What is radiotherapy?

Since the discovery of x-rays over one hundred

years ago, radiation has been used increasingly in medicine, both to help with

diagnosis (by taking pictures with x-rays), and as a treatment (radiotherapy).

While radiation obviously has to be used with care, doctors and radiographers

have great experience in its use in medicine.

Radiotherapy treatment can cure some cancers

and can reduce the chance of a cancer coming back after surgery, but can cause

side effects. It can be used to reduce cancer symptoms. The benefits and

possible side effects are discussed in detail below. Radiotherapy treatment can cure some cancers

and can reduce the chance of a cancer coming back after surgery, but can cause

side effects. It can be used to reduce cancer symptoms. The benefits and

possible side effects are discussed in detail below.

Radiotherapy is the use of x-rays and similar

rays (such as photons) to treat disease. Many people with cancer will have

radiotherapy as part of their treatment. This can be given either as external

radiotherapy from outside the body, using x-rays or

cobalt irradiation, or from within the body as

internal radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy works by destroying the cancer

cells in the treated area. Although normal cells are also sometimes damaged by

the radiotherapy, they can repair themselves more effectively.

External radiotherapy

External radiotherapy is normally given as a

series of short daily treatments in the radiotherapy department, using equipment

similar to a large x-ray machine. department, using equipment

similar to a large x-ray machine.

The treatments are usually given from Monday

to Friday, leaving patients to rest at the weekend. Each treatment is called a

fraction. Giving the treatment in fractions ensures that less damage is

done to normal cells than to cancer cells. The damage to normal cells is mainly

temporary, but is the reason why radiotherapy has some side effects.

The number of treatments you have depends on

several factors, including:

- your general health

- the site and type of cancer being treated

- whether or not you have had, or are going

to have, surgery, chemotherapy or hormonal therapy as part of your treatment.

For these reasons, treatment is planned for

each patient individually, and even people with the same type of cancer may have

different treatments.

External radiotherapy does not make you

radioactive, and it is perfectly safe for you to be with other people, including

children, throughout your treatment.

A course of curative (radical) treatment may

be given every weekday from two to six weeks. Instead of having one treatment a

day or having a rest at the weekend, some people will have different treatment

plans. They may have more than one treatment a day or treatment every day for

two weeks. Giving radiotherapy in this way is known as continuous

hyperfractionated radiotherapy (often called CHART).

Sometimes treatment may be given on only three

days each week (for example, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays). Palliative treatment (for symptom control) may

involve only one or two sessions of treatment, or up to five sessions.

The different types of radiotherapy machine

work in slightly different ways. Some are better for treating cancers near the

surface of the skin, while others work best on cancers deeper in the body.

The

type of radiotherapy machine used will be carefully chosen by your specialist

and physicist to give you the most appropriate treatment. Some machines are

quicker than others and may give treatment in a very short time, such as a few

seconds. Usually, radiotherapy treatment (including the time taken to position

you) takes 10-15 minutes or less, on any machine. The

type of radiotherapy machine used will be carefully chosen by your specialist

and physicist to give you the most appropriate treatment. Some machines are

quicker than others and may give treatment in a very short time, such as a few

seconds. Usually, radiotherapy treatment (including the time taken to position

you) takes 10-15 minutes or less, on any machine.

The radiotherapy machine does not normally

touch you and the treatment itself is painless, although it may gradually cause

some uncomfortable side effects. If you have a specific type of radiotherapy

known as electron treatment, a small applicator may be used, which touches a

small area of skin.

People react to radiotherapy in different

ways: some find that they can carry on working, taking time off for their

treatment, while others find it too tiring and prefer to stay at home. If you

have a family to look after, you may find that you need extra help. Don't be

afraid to ask for help, whether it's from your employer, family or friends,

social services, or the staff in the radiotherapy department. As your treatment

progresses, you will have a better idea of how it makes you feel so you can make

any necessary changes to your daily life.

The radiotherapy staff will try to give you an

appointment for the same time each day. This gives your body a chance to recover

from any side effects between treatments and also allows you to get into a daily

routine.

Internal radiotherapy

Internal radiotherapy is used mainly to treat cancers in the head and neck area,

the cervix, the womb, the prostate gland or the skin.

Treatment is given in one of two ways: either by putting solid radioactive

material (the source) close to or inside the tumour for a limited period of

time, or by using a radioactive liquid, which the patient takes either as a

drink or as an injection into a vein.

If you have internal radiotherapy, you may have to stay in hospital for a few

days and some special precautions will have to be taken while the radioactive

material is in place in your body. Once the treatment is over there is no risk

of exposing your family or friends to radiation.

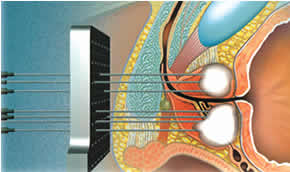

The process of putting solid radioactive material close to or inside the tumour

is called brachytherapy.

Giving a radioactive liquid, either as a drink, in a capsule or given as an

injection into a vein is called radioisotope treatment. Your specialist will

discuss your particular treatment with you. Before having your treatment you

will be asked to sign a form to say that you give your permission. brachytherapy.

Giving a radioactive liquid, either as a drink, in a capsule or given as an

injection into a vein is called radioisotope treatment. Your specialist will

discuss your particular treatment with you. Before having your treatment you

will be asked to sign a form to say that you give your permission.

Radioactive isotopes

Because of the possibility of unnecessary radiation exposure to the hospital

staff and your friends and relatives, certain safety measures are taken while

you are being treated with the radioactive source, or after you have been given

a liquid radioisotope. Depending on the type of treatment you are receiving,

this means the restrictions may be needed for a few days. But sometimes they are

only needed for a few minutes.

The staff looking after you will explain these restrictions to you in more

detail before you start your treatment. Each hospital has different routines,

and it is worth visiting beforehand to discuss what will happen with the nursing

and medical staff.

You may be admitted to the ward the day before your treatment so the staff can

go over the procedure with you. This is a good time to ask questions and it may

help to make a list beforehand so you don't forget something important.

While the radioactive source is in place, or after treatment with a liquid

radioisotope:

You will probably be nursed in a side room, away from the main ward. You may be

nursed alone or with someone else having similar treatment. Lead screens may be

placed on either side of your bed to absorb any radiation that is given out. The

doctors and staff on the ward will only stay in your room for short periods at a

time. Staff and visitors will be asked to stand away from your bed to reduce

their exposure to the rays.

If you are being treated with a radioactive source, the safety measures are only

necessary while it is in place. Before and after your treatment, your visitors

can come at normal visiting times.

Some people worry that they will remain radioactive once the treatment is over,

and be dangerous to their family and friends. If you have been treated with a

radioactive source, this is not so. As soon as the radioactive source has been

removed, all traces of radiation disappear. Some people worry that they will remain radioactive once the treatment is over,

and be dangerous to their family and friends. If you have been treated with a

radioactive source, this is not so. As soon as the radioactive source has been

removed, all traces of radiation disappear.

If you have been given a liquid treatment, however, the radioactivity will

disappear gradually. Before you leave hospital the staff will check that most of

the radioactivity in your body has gone, and that your belongings are free of

any signs of radioactivity. After you leave hospital you should be able to carry

on your life almost as normal, but there may be a few restrictions about meeting

people - especially children and pregnant women - for a few more days.

Caesium insertion

This type of internal radiotherapy treatment is used for treating cancer of the

cervix, uterus or vagina. The radioactive source most commonly used is called

caesium-137. The advantage of caesium insertion treatment is that it gives a

high dose of radiotherapy directly to the tumour, but gives a low dose to normal

tissues.

The caesium source has to be put inside an applicator (there may be more than

one) to keep it in place. The applicator, is inserted into the vagina, while you

are under a general anaesthetic or sedation in the operating room. At the same

time, a flexible tube called a urinary catheter may be put into your bladder to

drain off urine. This means you don't have to get on and off bedpans and risk

moving the applicators. Once the applicators are in place an X-ray will be taken

to check they are in the correct position. Sometimes the radioactive source is

put into the applicator while you are in the operating room, but more commonly

it will be put in place once you are back on the ward. You may hear this

referred to as 'afterloading'.

The applicators are kept in place by a pack (cotton/gauze padding) inside your

vagina. This can be uncomfortable and you may need to ask your nurse for regular

painkillers.

Once the source is put into the applicators you have to stay in bed. This helps

to keep them in the correct position. If you need anything, you can call a

member of staff by using the call bell by your bed. If the source does get

dislodged, you should call the staff on the ward immediately.

Curitron/Selectron machine Curitron/Selectron machine

In some hospitals a machine, which may be called a Curitron or Selectron or

similar name, is used to put the radioactive material into the applicators. The

machine is attached by tubes to the applicators. When the machine is switched on

it passes small radioactive sources into the applicators. If the machine is

switched off, the source is pulled back inside the machine. The machine is kept

switched on throughout your treatment, except when someone needs to go into your

room. It can then be turned off, so reducing their exposure to the rays.

However, safety measures and visiting restrictions are still necessary. The time

you spend on the machine varies but it is usually between 12 and 48 hours.

Microselectron

Sometimes a machine called a Microselectron can be used to give internal

radiotherapy. This gives the radiotherapy more quickly, so the treatments last

for only a few minutes and you can go home the same day.

After the treatment

Once you have received your dose of radiation the sources and the applicators

will be removed. This is usually done on the ward. As it can be a little

uncomfortable, you will be offered some painkillers beforehand. Sometimes a few

breaths of the gas Entonox will help you to relax. The staff on the ward check

that all the applicators and sources have been removed. Your catheter may be

removed at the same time.

Your doctor may suggest you use vaginal douches for a few days after the

insertion has been removed to keep the vagina clean. Your nurse will show you

how to use these. You will probably be able to go home the same, or the

following, day. Once the radioactive sources are removed, all traces of

radioactivity will immediately disappear.

Side effects

Many women will be treated with both internal and external radiotherapy to

ensure the area is treated in the most effective way.

There is a slight risk of infection following caesium insertion but this is very

rare. If you do develop a high temperature or heavy bleeding after your

treatment you should contact your doctor as soon as possible. You will be

prescribed antibiotics to deal with the infection.

Caesium or iridium implants

These can be used to treat a number of tumours including those in the mouth, lip

and breast. Very fine needles, wires or tubes carry the radioactive source, and

are inserted while you are in the operating room under a general anaesthetic.

An X-ray may be taken to ensure that they are in the correct position. You will

be nursed in a separate room, and safety measures will be applied until the

wires are removed, usually between three and eight days. Sometime this is done

under general anaesthetic.

Implants in the mouth can be uncomfortable, and can make eating and talking

difficult. A soft or liquid diet may be necessary while the needles are in

place. Your nurse will show you how to keep your mouth clean, using regular

mouthwashes. If eating is a problem you may be fed through a thin tube (nasogastric

tube) which is passed via your nose and into your stomach.

The implant is removed once the correct dose of radiation has been received.

This may be after two days, if the treatment is given as a booster after

external treatment, or up to one week if given as the only form of treatment.

Once the implant has been removed the area will feel sore for up to two or three

weeks afterwards. Your specialist will prescribe pain killers that you can take

regularly until this improves.

Radioactive seed implants are occasionally used to treat small tumours of the

prostate gland. See the section on cancer of the prostate that explains this

treatment in more detail. Radioactive seed implants are occasionally used to treat small tumours of the

prostate gland. See the section on cancer of the prostate that explains this

treatment in more detail.

Radioactive isotopes

These are given as liquids, either through the mouth (in capsules or as a drink)

or by injection into a vein (called an intravenous injection). The commonest

form of radioisotope treatment is radio-iodine. It is used to treat tumours of

the thyroid gland, and is given in the form of an odourless and colourless

drink.

The same safety precautions will be taken with this type of treatment as with

implants.

Any radio-iodine which is not absorbed by your thyroid will be passed from the

body in sweat and urine. You should drink plenty of fluids during your treatment

as this helps to flush the iodine out of the body. The amount of radiation in

your body will be checked regularly and as soon as it falls to a safe level,

after about four to seven days, you will be able to go home. You may need to

take some special precautions for a short time after going home - particularly

with young children and pregnant women. The hospital staff will explain these to

you.

Radioisotope treatment can also be given when certain types of cancer have

spread to the bones (secondary cancer in the bone). A radioisotope is injected

into a vein and this is normally given as an out-patient. Before you go home you

will be given some simple advice to follow as your urine and blood are slightly

radioactive for a few days. The section

on secondary bone cancer has more information on this treatment.

More on Side Effects

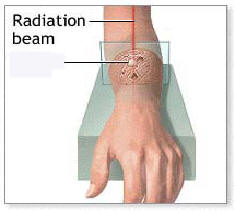

Cancer cells usually multiply

faster than other cells in the body. Since radiation is most harmful to rapidly

reproducing cells, radiation damages cancer cells more than the normal cells of

the body. It prevents these cells from continuing to reproduce and thus prevents

the tumour from growing further.

Unfortunately, rapidly dividing healthy cells can also be killed by this

process. Skin and hair are some of the tissues most noticeably affected by

radiation treatment, resulting in skin lesions, burning, redness, and possibly

hair loss. Unfortunately, rapidly dividing healthy cells can also be killed by this

process. Skin and hair are some of the tissues most noticeably affected by

radiation treatment, resulting in skin lesions, burning, redness, and possibly

hair loss.

Radiation therapy is used to fight many types of cancer. Often it is used to

shrink the tumour as much as possible before surgery to remove the cancer.

Radiation can also be given after surgery to prevent the cancer from coming

back.

For certain types of cancer, radiation is the only treatment needed. Radiation

treatment may also be used to provide temporary relief of symptoms, or to treat

malignancies (cancers) that cannot be removed with surgery.

The following are some commonly used radioactive substances:

Caesium (137Cs) -

Cobalt (60Co) -

Iodine (131I) -

Phosphorus (32P)

Gold (198Au) -

Iridium (192Ir) -

Yttrium (90Y) -

Palladium (109)

Radiation therapy can have many

side effects. These side effects depend on the part of the body being irradiated

and the dose and schedule of the radiation:

Fatigue and malaise

Low blood counts

Difficulty or pain swallowing

Erythema

Oedema

The shedding or sloughing-off of the outer layer of skin (desquamation)

Increased skin pigment (hyper-pigmentation)

Atrophy

Skin itching (pruritus)

Skin pain

Changes in taste

Anorexia

Nausea

Vomiting

Hair loss

Increased susceptibility to infection

Foetal damage (in a pregnant woman) |